Authors: Kaspersky Lab and the Oxford University Functional Neurosurgery Group

There is an episode in the dystopian near-future series Black Mirror about an implanted chip that allows users to record and replay everything they see and hear. A recent YouGov survey found that 29% of viewers would be willing to use the technology if it existed.

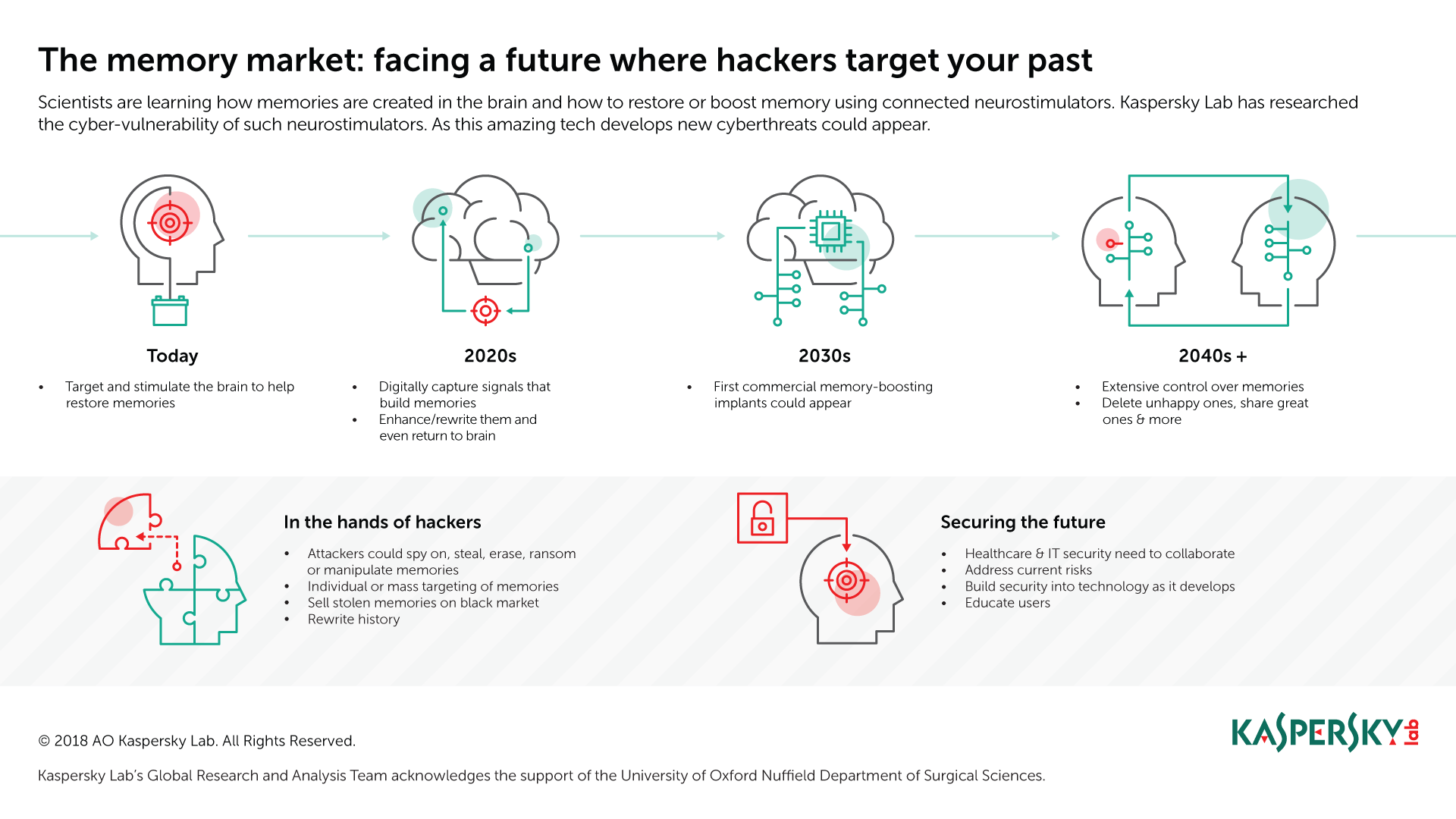

If the Black Mirror scenario sounds a bit too much like science fiction, it’s worth noting that we are already well on the way to understanding how memories are created in the brain and how this process can be restored. Earlier this year proof of concept experiments showed that we can boost people’s ability to create short-term memories.

The seeds of the future are already here

The hardware and software to underpin this exists too: deep brain stimulation (DBS) is a neurosurgical procedure that involves implanting a medical device called a neurostimulator or implantable pulse generator (IPG) in the human body to send electrical impulses, through implanted electrodes, to specific targets in the brain for the treatment of movement and neuropsychiatric disorders. It is not a huge leap for these devices to become ‘memory prostheses’ since memories are also created by neurological activity in the brain.

To better understand the potential future threat landscape facing memory implants, researchers from Kaspersky Lab and the University of Oxford Functional Neurosurgery Group have undertaken a practical and theoretical threat review of existing neurostimulators and their supporting infrastructure.

The attached report is the outcome of that research. It should be noted that because much of the work involving neurostimulators is currently handled in medical research laboratories, it’s not easy to practically test the technology and associated software for vulnerabilities. However, much can be learned from handling the devices and seeing them used in situ, and this research involved both.

Among other things, the researchers found existing and potential risk scenarios, each of which could be exploited by attackers. These include:

- Exposed connected infrastructure – the researchers found one serious vulnerability and several worrying misconfigurations in an online management platform popular with surgical teams.

- Insecure or unencrypted data transfer between the implant, the programming software, and any associated networks could enable malicious tampering of a patient’s implant or even whole groups of implants (and patients) connected to the same infrastructure. Manipulation could result in changed settings causing pain, paralysis or the theft of private and confidential data.

- Design constraints as patient safety takes precedence over security. For example a medical implant needs to be controlled by physicians in emergency situations, including when a patient is rushed to a hospital far from their home. This precludes use of any password that isn’t widely known among clinicians. It also means that by default such implants need to be fitted with a software ‘backdoor’.

- Insecure behavior by medical staff – programmers with patient-critical software were being accessed with default passwords, were used to browse the internet or had additional apps downloaded onto them.

Future risk predictions

Within five years, scientists expect to be able to electronically record the brain signals that build memories and then enhance or even rewrite them before putting them back into the brain. A decade from now, the first commercial memory boosting implants could appear on the market – and, within 20 years or so, the technology could be advanced enough to allow for extensive control over memories.

The healthcare benefits of all this will be significant, and this goal is helping to fund and drive research and development. However, as with other advanced bio-connected technologies, once the technology exists it will also be vulnerable to commercialization, exploitation and abuse.

New threats resulting from this could include the mass manipulation of groups through implanted or erased memories of political events or conflicts; while ‘repurposed’ cyberthreats could target new opportunities for cyber-espionage or the theft, deletion of or ‘locking’ of memories (for example, in return for a ransom).

Conclusion

Current vulnerabilities matter because the technology that exists today is the foundation for what will exist in the future. Although no attacks targeting neurostimulators have been observed in the wild – a fact that is not altogether surprising since the numbers currently in use worldwide are low, and many are implemented in controlled research settings, several points of weakness exist that will not be hard to exploit.

Many of the potential vulnerabilities could be reduced or even eliminated by appropriate security education for clinical care teams and patients. But healthcare professionals, the security industry, the developers and manufacturers of devices and associated professional bodies all have a role to play in ensuring emerging devices are secure. We believe that collaborating to understand and address emerging risks and vulnerabilities, and doing so now while this technology is still relatively new, will pay off in the future.

“Security assessment of corporate information systems in 2017” full report (PDF)

“Security assessment of corporate information systems in 2017” full report (PDF)

No comments:

Post a Comment